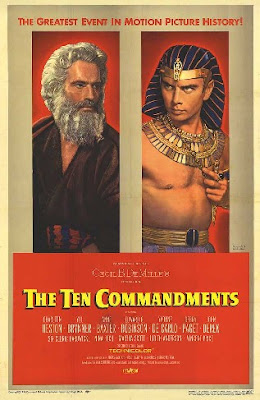

De Mille’s importance to us here is that he epitomizes for that time what an American celebrity was. Yet, the reality is that he was a Flemish American. This of course speaks to the issues of assimilation and self-identity (I have not seen any article or statement where De Mille publicly acknowledged his Flemish roots). Be that as it may, DeMille is a direct descendant of Flemish emigrants. The important point here, of course, is that DeMille’s genealogy speaks to the unacknowledged presence (and prominence) of Flemish Americans.

Permit me then to offer to you, on this anniversary of his passing, an abrdiged and edited reprinting of the Flemish origins of the DeMilles (edited by me for style but content primarily excerpted from Louis P. de Boer’s “Pre-American Notes on Old New Netherland Families,” from The Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey, Volume III/1928).

Anthony deMil/DeMille (1625-1689) is the first of his family name to reside in America.[i] He is a direct ancestor in the male line of Cecil B. DeMille (1881-1959). The De Milles belonged to the colony of Flemish refugees which had established itself at Haarlem after 1577, just after that city had freed itself from Spanish control.[ii] The Flemish colony at Haarlem had grown as a result of immigration, by numbers of settlers, either directly from Flanders, or from Flemish refugee colonies in England and Germany.[iii]

The persecutions of dissenters [such as the Pilgrims, who of course fled England for the Netherlands in 1607] by the British King James I caused many Flemings to flee England and relocate in Haarlem. Even at that time this was remarked upon. In the Haarlem city archives there is a thin booklet called [translated into English] “An Account of the Flemings who have come to the city of Haarlem in the year 1612”.[iv]

Of the Flemish refugees at Haarlem, the largest numbers appear to have come from Brugge (Bruges), Gent (Ghent) and Antwerp.[viii] For the first few generations this Flemish community kept up their Flemish traditions and customs and frequently intermarried. When they emmigrated abroad, these practices were carried over to New Netherland. In fact, many of these Haarlem Flemings settled in New Netherland beginning around the middle of the 17th century.

The Flemish Haarlem family we are most interested in, the De Mille family, was originally from Brugge (Bruges), in West Flanders. For example: a certain Gerard de Mille lived at Brugge in 1350; a Jan de Mille lived there in 1400 and a Martin de Mille was a resident at Brugge in 1550. Some members of the De Mille family were wholesale flour and grain merchants. This appears to be a profession passed from father to son. A branch of the family also existed at Antwerp.[ix]

Like his father before him, Anthony de Mille (grandfather of Anthony De Mille the New Netherlander) was born at Brugge about 1550. There he married Maria Cobrysse [perhaps sometime in the late 1570s or early 1580s]. Maria was the daughter of Jacob Cobrysse and his wife Jacomyntje. Maria’s mother’s sister [name unknown] married a Matthys van de Walle. Sometime before 1597 both Anthony de Mille and his wife Maria Cobrysse died and their minor children were taken in by their great uncle Matthys de Walle.

Anthony de Mille the Younger at some point gravitated back to the “half-Flemish city” of Haarlem. For it was at the Dutch Reformed Church at Haarlem on September 19, 1653 that Anthony de Mille the Younger married Elisabeth van der Liphorst, a lady of Flemish origins residing at Haarlem.[x] Both bride and groom had lived on the Anegang, a narrow street still used in Haarlem.

Like some of his ancestors, Anthony de Mille the Younger made his living as a grain merchant. This required frequent travel. But since the grain trade was closely tied into the financial exchange at Amsterdam, it is likely this which pulled the young family from Haarlem to Amsterdam. It was in Amsterdam in the following year, 1654, that the couple’s first child (named Maria, after her paternal grandmother as was the practice) was born.

The next child we know of from the notarial records was born and baptized in Haarlem. The translated entry reads:

21 August 1657 Father: Anthony de Mil of Haarlem Mother: Elisabeth van der Liphorst

ANNA Witnesses: Jacob van de Water & Elisabeth van der Schalcken

On May 15, 1658) the de Mille family left for America.[xii] Anthony de Mille and his family sailed from Amsterdam in Holland for New Amsterdam in New Netherland on the ship De Vergulde Bever (The Gilded Beaver).[xiii] The family included Anthony, his wife Elisabeth van der Liphorst, and their children, Maria (aged 4) and Anna (9 months).[xiv]

However, this soon changed. In quick succession Anthony and Elisabeth added three sons and another daughter to their brood.

7 December 1659 Parents: Anthony de Mill Lysbeth van der Liphorst

ISAAC Witnesses: Govert Loockermans & Neeltje de Nys

12 October 1661 Parents: Anthony de Mill Lysbeth van Liphorst

PETRUS Witnesses: Johannes van Brugge & Cornelia de Peyster

30 December 1663 Parents: Anthony de Mill Lysbeth van der Liphorst

SARA Witnesses: Hendrick van de Water & Ytie Strycker

14 March 1666 Parents: Anthony de Mill Lysbeth van der Liphorst

ANTHONY Witnesses: Johannes de Peyster & Catharina Roelofs

It is remarkable that most of the baptismal witnesses named above had Flemish names, although Govert Loockermans is the only one actually born in modern-day Flanders (Turnhout).[xv] The last three named – Van Brugge, de Peyster, and van der Water – all belonged to the Haarlem-Flemish diaspora that resettled in New Netherland.[xvi]

Once in New Netherland, Anthony de Mille earned his daily bread (literally) as a baker. It is possible that de Mille was even involved in baking Sinterklaas cookies for the half-Flemish Maria van Rensselaer http://flemishamerican.blogspot.com/2011/12/flemish-claim-to-sinterklaas-in-america.html While baking seems to be a safe occupation, de Mille did seem to get into trouble. Noted New Netherlands historian Dr. Jaap Jacobs cites an example where de Mille (whose name is incorrectly transcribed as “de Milt”) is fined 150 guilders for baking bread lighter than regulations.[xvii]

Anthony de Mille’s will, dated May 27, 1689, was proved December 10, 1689, and confirmed by Governor Leisler January 4, 1690. The will names him “a merchant living in the City of New York, and a widower.” It mentions his children and his housekeeper, Mary Winter [as heirs]. While locally prominent to various degrees, none of these de Milles ever reached real prominence. Little did they all know that one day a direct descendant would claim the world stage.

Endnotes

[i] There appears to be a great deal of misinformation floating around on DeMille, his birthplace, his ancestors, etc. (from websites – cf http://www.geni.com/people/Anthony-Demill/6000000000609950526 and http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~jmthompson/Roads/familygroup/fg03_203.htm ). Thus, the genealogies associated with these names are always suspect unless one has the documentation as verification. So,permit me to offer a disclaimer: with the exception of the sources I include below, I am not able to verify the full genealogical contents of Louis de Boer’s article.

[ii] Haarlem was besieged by the Spanish and after capitulating, the surrendering Netherlandic troops were butchered and the city sacked by the Spaniards. In 1577 the Agreement of Veere was signed that granted equal rights to both Catholics and Protestants. The accord lasted for a year before Catholicism was forbidden. The ebb and flow of the Dutch Revolt/Eighty Years War is difficult to follow and not treated in any recent books in English that I am aware of. The two best authorities (in English) are Geoffrey Parker, The Dutch Revolt, (Norwich: Penguin Books, 1977) and Pieter Geyl, The Revolt of the Netherlands, 1555-1609, (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1980). Sadly, Jonathan I. Israel, The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall, 1477-1806, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), fails miserably for anyone who seeks to understand the timeline of the period. Israel also appears shockingly oblivious to the major contribution of Zuid Nederlanders to the rise and greatness of the Dutch Republic.

[iii] Please see a nice article here on the Flemish influence on Haarlem (in Dutch): http://www.trouw.nl/tr/nl/4324/nieuws/article/detail/1083652/2010/01/16/Vlaming-in-Haarlem.dhtml . For the definitive overview in Dutch on the Flemings in Haarlem, see also P. Biesboer, et.al., Vlamingen in Haarlem, (Haarlem: De Vrieseborch, 1996).

[iv] Unfortunately I have been unable to locate a single reference to such a book anywhere. This leads me to wonder if the good Mr. DeBoer might have mistranscribed the reference. The only document that I am aware of is Pieter van Hulle’s 1642 Memoriaal van de Overkomste der Vlamingen hier binnen Haarlem.Incidentally (and unfortunately) Van Hulle’s “Memoriaal” is not on Google books.

[v] See Geoffrey Parker, The Thirty Years’ War, (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984).

[vi] A good online source and summary of the history of the Palatine as it relates to immigrants to America in the 17th century can be found here: http://www.olivetreegenealogy.com/palatines/palatine-history.shtml

[vii] See Dr. J. Briels, Zuid-Nederlanders in de Republiek, 1572-1630: Een demografische en cultuurhistorische studie, (Sint-Niklaas, Danthe, 1985), “Tabel XXI: Immigratie in de Noordelijke Nederlanden-Samenvatting”, p.214. Dr. Briels shows that several other cities which contributed large numbers of immigrants to America – Leyden and Middleburg each had more than 50% immigrants from modern day Belgium in 1622. Even Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Gouda were reckoned to have more than 30% Zuid-Nederlanders. For Dr. Briel’s analysis of the composition of the Flemish influx to Haarlem during this time see ibid, pp.107-116.

[viii] In this respect De Boer is not basing his claim on statistics. Dr. J. Briels, Zuid-Nederlanders in de Republiek, 1572-1630: Een demografische en cultuurhistorische studie, (Sint-Niklaas, Danthe, 1985), “Tabel XXI: Immigratie in de Noordelijke Nederlanden-Samenvatting”, in his “Tabel II: Immigratie in Haarlem – 1578-1609. Bron: lidmatenboeken van de calvinistische gemeente” p.112, refugees from Gent (234) and Antwerp (225) far exceeded those from Brugge (60). Even Tielt (76), Menen (75), Roeselare (74), and Kortrijk (66) exceeded those listed as from Brugge. However, the greatest number (453) simply said they were from “Vlaanderen”.

[ix] De Boer goes onto say: “In the old Abbey-Church of St. Michel at Antwerp there is a tombstone with the following inscription (translated): ‘Here lies buried, Francois de Mil, Lord of Westerem and Faerden.” Mr. de Boer goes onto offer an inscription at the church and other details. Unfortunately, the closest example to a church that fits that description that I am able to uncover is this church in Antwerp: http://www.topa.be/site/216.html. The Wikipedia description is a bit clearer: http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sint-Michielsabdij_(Antwerpen) However, according to the history, the church was demolished by Napolean’s troops preparing for a crossing of the English Channel in the 1790s. So it is very hard to place the actual details of this transcription. Parenthetically, the fief that this Francois de Mil was theoretically suzerain over appears to be now a part of Gent, not Antwerp: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sint-Denijs-Westrem .

[x] In the Haarlem Art Museum there is an oil painting of a Maria van der Liphorst who appears to have been a sister. Their mother’s maiden name was Van Brugh or Van Brugge. See http://wingetgenealogy.com/tree/family.php?famid=F2642&show_full=1

[xi] Louis de Boer cites Document #280 of the City Archives of Haarlem as the source. Per de Boer, this was notarized by W. van Kittensteyn and witnessed by Anthony de Mil and Jan Thomas van Son). For an interesting look at the importance of notaries in the lives of Netherlanders and New Netherlanders see Donna Merwick, Death of a Notary: Conquest and Change in Colonial New York, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999). Note that the main protagonist in Merwick’s tale, Ludovicus Cobus, is a native of Herentals, in the Province of Antwerp.

[xii] Ship sailings can be found online here http://immigrantships.net/newcompass/pass_lists/listolivetree2.html for New Netherland bound passengers.

[xiii] The ship passenger lists for those sailing to New Netherland at this time can be found here: http://www.olivetreegenealogy.com/nn/ships/

[xiv][xiv] The family name was mis-transcribed as “de Mis”. Also on board was Jan Evertsen from Lokeren, East Flanders. See http://www.olivetreegenealogy.com/ships/nnship05.shtml For a detailed (and crisply accurate) genealogy and documentary trail of Jan Evertsen of Lokeren and the Ten Eyck and Boel families of Antwerp, please see Gwen F. Epperson, New Netherland Roots, (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1994), especially pages 3-4 for Jan Evertsen, Appendix C, “The Ten Eyck-Boel European Connection” (pp.123-129).

[xv] The 400th anniversary of Govert Loockermans’ birthday is July 2nd, 2012. I intend to have a blog post about Loockermans completed by that time.

[xvi] The de Peysters were originally from Gent. The Van Brugges originally from Brugge. The Van der Waters may also have been from Brugge. The van de Waters participated in De Mille family baptisms both in Haarlem and in New Amsterdam. Johannes Van Brugges has been listed as a relative of the De Milles, according to de Boer.

[xvii] Jaap Jacobs, New Netherland: A Dutch Colony in Seventeenth-Century America, (Leiden: Brill, 2005), pp.248-249: “Baker Anthony de Milt [sic] was accused by the Schout Pieter Tonneman of baking bread that was too light in weight. De Milt did not deny that his bread was below standard, but maintained that this was not deliberate. According to him the batch had been left in the oven for too long. His explanation was supported by his assistant, Laurens van der Spiegel, who declared that the bread had been in the oven for four hours, an hour longer than normal. This had happened while De Milt [sic] was out on business and Van der Spiegel was busy in the loft. Furthermore, the batch consisted of only forty loaves instead of the usual seventy. And since bread from between sixty and seventy schepels [about fifty bushels] of grain had been baked during the previous days, the oven was very hot. The result of all this was that the bread became too dry, and consequently weighed less than it should have. Other bakers consulted by the court stated that this was a plausible explanation. Burgemeesters and Schepen nonetheless sentenced De Milt to a fine of one hundred and fifty guilders, but rejected the demand by Schout Tonneman that he be banned from baking for six weeks, probably because they were convinced that this was not a case of deliberate attempt to defraud.” Parenthetically, while I am generally delighted with the breadth and scope (and scholarship) of Dr. Jacobs’ New Netherland, his book retains the critical flaw of many Dutch-centric books: ignoring or glossing over the contributions of the Flemish.

Copyright 2012 by David Baeckelandt. All rights reserved. No reproduction in any format permitted without my express, written consent.

__Portrait_of_a_Woman.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)