Timeline of Flemish Discovery & Settlement of North America

·862-864 Baldwin Iron Arm establishes the County of Flanders in response to the depradations of Norsemen

·600s Sint Baaf (Saint Bavo) helps establish Christianity in Flanders

·800s St Ansgar of Tourhout becomes the first Catholic missionary to make a dedicated evangelization effort to Scandinavia (and some claim as far as Greenland)

·982-985The Norseman Eric the Red founds a colony in western Greenland; the settlement lasts until the fourteenth or fifteenth century.

·990-999Dankbrand, a Flemish missionary from Tourhout (and the Archbishop of Bremen, which diocese at that time explicitly included Scandinavia, Iceland and Greenland) converts first King Olaf of Norway and then Leif Ericsson

·c. 1000Leif Ericsson, returning to Greenland from Norway, is driven onto the North American coast, which he explores and tries unsuccessfully to settle. With Leif is a “Southlander” [e.g., German/Dutch/Flemish] Catholic priest named “Dirck” who gives Vineland its name.

·1147 Burgundian knightRaymond de la Coste, as a reward for serving the King of Portugal, Afonso I, in the siege of Lisbon, is granted a fief and the surname Corte Real.

·1297 Flanders is the first maritime nation to be accorded the honors of a naval salute (by England, via treaty)

·1302 Guldensporenslag/Battle of the Golden Spurs (July 11th)

·1320-1350 Jan de Langhe of Ieper writes The Travels of John Mandeville– which inspires Columbus & later explorers

·1327 Jan d’Ypres from Bruges purchases approximately 1500 pounds of walrus tusks from the archbishop of Nidarios who had received the tusks as tithes from Greenland (August 11th).

·1364 Jacobus Cnoyen pens the Inventio Fornato which describes the Arctic cartographic discoveries of a “fifth-generation Bruxellois” priest resident in Greenland. This is a book that inspires Columbus, Ruysch, Mercator, and the English thru John Dee to seek a northwest passage to Asia.

·Early 1400s “The use of the initials of the Frankish names of the winds – N, NNE, NE, etc. – on compass cards, seems to have arisen with Flemish navigators, but was early [1400s] adopted by the Portuguese and Spanish.”

·1427 circa Azores discovered by a Joshua Vander Berg of Bruges

·1429 Columbus’ father Domenico, at the age of 11, is apprenticed to a Flemish weaver from Brabant

·1447 Dirck Maartens, first printer in the Low Countries, is born at Aalst.

·1450 Jacome de Bruges (aka, Jacques/Jaak van Brugge) is granted a donatory as Capiton Terceira (March 2nd) by Prince Henry the Navigator.

·1450s-1470s Thousands of settlers from the Franc of Brugge emigrate to the Azores under the sponsorship of Prince Henry’s sister, Isabel, Duchess of Burgundy; the last European settlers die in Greenland – gravesite excavations uncover the latest Flemish fashions of 1450-1470 Flanders: pleated dresses for the women and conical hoods for the men.

·1460-1470 Joost Van Hurtere becomes lord/captain of the islands of Fayal and Pico (dies 1495).

·1471 1st printed book in the Low Countries (at Aalst); Alvaro Martins Homem granted captaincy of Angar region of Terceira

·1474 First book in English printed at Brugge by William Caxton (who calls the Flemish, one of the seven races of the British Isles); Jacome de Bruges dies (April 2nd); Joao Vaz Corte Real and his Flemish partner, Alvaro Martins Homem, are granted (for maritime services rendered) governorship of Terceira, Azores, by the widow of Prince Fernando (February 12th).

·1476 Columbus embarks on his first voyage – on a Flemish urca called the Bechalla bound for Flanders: it is attacked and sunk by the French pirate Casenove off the coast of Portugal (August 13th)

·1470s Willem Van der Haegen (aka Silveiras) becomes lord/captain of the island of Flores (most northwesterly of the Azores)

·1483 Joao Vaz Corte Real also granted governorship of the island of S. Jorge in the Azore islands

·1484 Columbus demands King John II of Portugal supply ships and men to discover the Indies sailing West

·1486 Ferdinand Van Olmen and Joham Afonso do Estreito agree to split 50/50 the rights to lands granted Van Olmen by King John II of Portugal (June 12th– ratified by king July 24th) to find the Islands of the Seven Cities

·1487 Ferdinand Van Olmen sent out in a northwesterly direction by March; later Van Olmen becomes lord/captain of the area on Terceira Island called Ribeyras; King John II also sends out Bartolomeu Dias around the south coast of Afgrica and Afonso da Pavia across the north coast of Africa (both to seek a path to the Indies)

·1488 Bartolomeu Dias returns first to Spain, then Portugal, proving that the Indies can be reached by sailing around the southern tip of Africa (December)

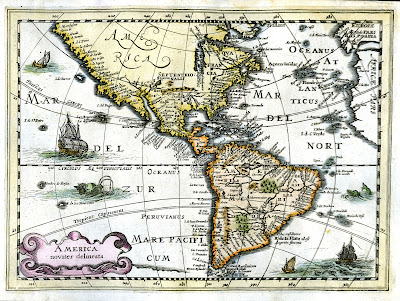

·1492 Columbus granted rights to seek out a westward path to the Indies (April 17th); and “discovers” America (October 12th). His two most heavily annotated “guide books” are The Travels of John Mandeville (written by Fleming Jan De Langhe) and the Discoveries of Marco Polo (printed at Antwerp in 1475). His most common trade item is Flemish bells; his most important cartographic tool is the Flemish language compass rose (with a “Flemish needle”). Martin Behaim, a son-in-law of Joost van Hurter of Moerkercken/Winendaele, West Flanders (the Flemish Lord of first Fayal/Neu Flandern and then Pico in the Azore Islands) and the cartographic advisor to the King of Portugal, creates the oldest existing globe on which he describes the Flemish Azorean discoverers of islands in the Indies (September)

·1493 Columbus returns from America (March 4th). First return land sightings are the ‘Flemish Islands’ aka, the Azores (February 12th). He pens a missive (officially dated March 14th) which is widely reprinted by Flemish printer from Aalst Dirck Maartens in Antwerp and Gerardus de Lisa [Gerard van de Lys, a Gentenaar] in Italy; On his second voyage Columbus takes two Franciscans from Ath, Henegouwen (September 24th).

·1494 The Pope awards Spain all lands west and Portugal all lands east of an imaginary line 100 leagues west of the Azores in the Treaty of Tordesillas (June 7th)

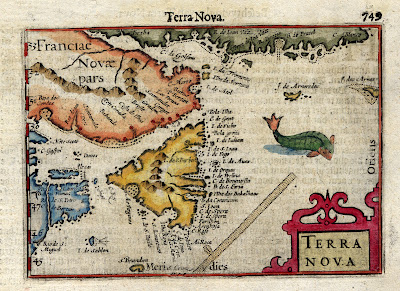

·1497 John and Sebastian Cabot depart Bristol, England (May 2nd) and arrive at Cape Breton Island (June 24th). They are guided by Joao Fernandez, the Labrador, “because he who gave the information to the King of England was a labrador of the Azores”; Johannes Ruysch of Utrecht & Antwerp is also believe to have been on the Cabots’ voyage.

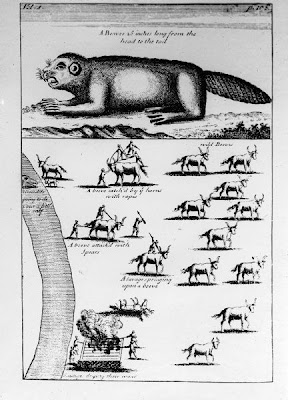

·1499 Miguel Corte Reale embarks from the Azores to “Terra Nova” [Newfoundland]. His fleet is shipwrecked on the Massachusetts coast but leaves distinct carvings on the Deighton Rock. Joham (Joao) Fernandes of Barcelos, near Van Olmen’s on Terceira, is granted the right, by King Manuel of Portugal, to search for and discover islands to the northwest (October 28th).

·1500 The future Charles V, first ruler of an empire on five continents, is born on the road near Eeckloo, East Flanders (February 24th); King Manuel grants Gaspar Corte Reale jurisdiction over all discovered lands and “enterprises that he now desires to continue;” he then sails (June) to Greenland and Newfoundland (returning before January 27, 1501).

·1501 Gaspar Corte Reale again departs Lisbon (May 15th) with three ships for Newfoundland; two return on October 8th/9th and October 12th (respectively).King Henry VII of England grants three Azoreans resident at Bristol (Joao and Francisco Fernandes and Joao Goncalves) letters-patent for any discoveries to the west (March 19th) thereby creating the “pioneer corporation of the British Empire”.

·1502 Cantino Map created by Flemish mapmaker (Breelant?) which shows Newfoundland as “Terra del Rey de portugall” (territory of the king of Portugal) – it also shows the Yucatan and Cuba years before they were officially “discovered”; The first recorded shipload of Newfoundland cod is brought back to England – by an Azorean Fleming; Miguel Corte Reale departs Lisbon for Newfoundland (May 10th) with three ships of which two return (August 20th); King John II of Portugal decides to sell all of his spices at Antwerp (instead of Bruges or Lisbon)

·1506 Christopher Columbus dies (May 20th)

·1507 Johannes Ruysch of Antwerp/Utrecht prints the very first printed global map that shows America and Newfoundland (“Terra Nova”), where it seems to have copied the Cantino map. Ruysch clearly borrows from Behaim’s 1492 globe and also relies on the Inventio Fortunata for information on a Northwest passage to Asia. Ruysch’s map becomes an important source for future cartographers such as Mercator; Waldseemueller’s map using the name “America” is printed [in 1513 Waldseemueller rejects the name “America”]

·1509 Joost Van Hurtere II becomes lord/captain of the islands of Fayal and Pico (May 31st)

·1511 Gerardus Mercator born at Rupelmonde, E. Flanders (March 5th); The very first book on the “discovery” of America in English, Peter Martyr’s “New Founde Landes”, is printed at Antwerp; Deighton Rock in Massachusetts is carved by Miguel CorteReale.

·1517 Adolf of Wynendaele (West Flanders) ferries Charles to Spain to assume the throne; Jan de Witte of Brugge is named Bishop of Cuba (August).

·1518 Adolf of Wynendaele (West Flanders) is granted ownership of the island of Cozumel off the coast of the Yucatan and therefore is named by Charles “Admiral of Flanders” and Governor of Cuba (March 29th); Laurrent de Gorrevod, Flemish majordomo for Emperor Charles V, requests a license for exclusive trade and to establish a colony on the Yucatan.

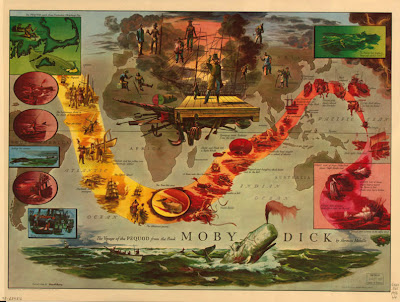

·1519-1522 Charles V funds Magellan’s circumnavigation of the world, which leaves Spain with 5 Flemings. Only 1, Roland van Brugge, survives.

·1520 One of the 5 Flemings of Magellan’s fleet, Roland van Brugge, becomes the first man of the fleet to see the Pacific

·1522 The 33 survivors (including Roland van Brugge after imprisonment in the Azores) return to Spain

·1523 Maximillanus Transylvanus of Brussels, after interviewing nearly all of the 33 survivors (including Roland van Brugge) of Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe – the world’s first – publishes the report (January 1st).

·1527 Abraham Ortelius, 1st cousin of Emanuel Van Meteren and Daniel Rogers, born at Antwerp (April 14th) dies in the same city, June 28th, 1598. Philip II of Spain also born and dies the same years as Ortelius (b May 21st at Vallodolid; dies September 13th, San Lorenzo).

·1533 Willem van Oranje born at Dillenburg (April 24th)

·1534 Dirck Maartens, first printer in the Low Countries, printer of Columbus’ copy of Marco Polo at Antwerp and of Columbus’ First Letter in 1493, as well as of Thomas More’s Utopia, dies at Aalst (May 2nd).

·1535 Corte Real voyages again launched; Emanuel Van Meteren born at Antwerp (July 8th).

·1538 Gerardus Mercator of Rupelmonde, East Flanders, creates a world map for the use of the world’s first global emperor, Charles V (born near Eeckloo, East Flanders) and uses – for the first time ever – the name “North America” for the current continent; Mercator also labels the channel between Canada and Greenland as the “Strait of the Three Brothers through which Portuguese attempted to sail to the Orient and the Indies and the Moluccas”. Manoel Corte Real, son of Vasco Eannes Corte Real (the 1st), declared “Lord of Terra Nova”.

·1545 ”It remains to be remarked that the Portuguese mariners at an early date seem to have adopted the Flemish designations of the winds…In the Arte de Navegar of Pedro de Medina (Valladolid, 1545), the Flemish names are given.”

·1550 “Dutch” Church established in London by Micronius of Ghent

·1552 Petrus Plancius born at Dranouter (near Ieper, West Flanders) – dies May 15th, 1622 in Amsterdam

·1555Abdication of Charles V in favor of his son Philip and brother Ferdinand; Philip II inherits control over the Low Countries; tensions between actual (Philip II) and emotional (Willem of Orange) sons evident at Brussels abdication; Muscovy Co in England established at London by Sebastian Cabot, John Dee, and depending upon

·1556 Dirck Van Os born in Antwerp (March 13th) – critical Fleming in the discovery and settlement of America (dies May 20th 1615 at Amsterdam).

·1558 Charles V dies (September 21st)

·1561 Manoel Corte Real, son of Vasco Eannes Corte Real (the 1st), prepares ships of Azorean settlers in Terceira to colonize Newfoundland – the colonization of Sable island; Samuel Godijn is born at Antwerp

·1563 Franciscus Gomarus, leader of the Counter-Remonstrant party, born at Brugge (January 30th); dies at Groningen, January 11th, 1641.

·1566Beeldenstorm (“Iconoclastic Fury”). Considered the start of the “Dutch Revolt” (De Opstand) begins in Steenvoorde, Flanders (August 10th), Spreads from Steenvoorde to the rest of the Netherlands. Nine Flemings and one Spaniard land near St. Augustine FL and spend 10 days there before seeking a Spanish settlement to the south (September 16th). Manoel Corte Real, son of Vasco Eannes Corte Real (the 1st), prepares ships of Azorean settlers in Terceira to colonize Newfoundland.

·1567 Manoel Corte Real, son of Vasco Eannes Corte Real (the 1st), prepares three ships of Azorean settlers in Terceira to colonize Newfoundland.

·1568 Azoreans begin colonization of Newfoundland in conjunction with Native American villages (March). Dutch nobles Egmont and Hoorn beheaded at Brussels; the Dutch revolt against Spain begins; Willem Usselinckx of Antwerp, whose life span in years mirrors exactly that of the Dutch Revolt, is born.

·1569 Gerardus Mercator creates his world map with “rhumblines” which solves a navigational problem (accounting for the curvature of the earth when plotting sailing routes on maps) that had caused mariners problems for centuries

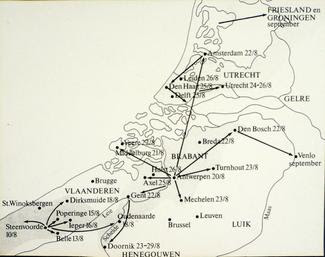

·1572 Expulsion of the Flemish and Dutch privateers (watergeuzen) from England (March 31st);Capture of Den Briel, strategic city at the mouth of the Rhine, by "Sea Beggars" led by the Flemish Admiral Lumey (April 1st); Abraham Ortelius, with guidance and assistance from his good friend Gerardus Mercator, creates the first “atlas” (which furthers navigation)

·1573Dutch defeat Spanish fleet at battle of Zuiderzee

·1574 Vasco Eannes Corte Real sails on the last known colonization voyage from the Azores to North America (Labrador). Relief of Leiden (Ontzet), on October 3rd made possible by the Antwerpenaar Moons and the Flemish-led watergeuzen (the commemoration of this event forms the basis of American Thanksgiving when the Pilgrims land in America). Pacification of Ghent (Pacificatie van Gent), November 8th unites all Netherlanders of all stripes against the Spanish

·1575 As a reward for resisting the Spanish siege, William of Orange permits Leiden to establish the first university of the northern Netherlands. The first President of the University is Justus Lipsius of Vilvoorde, Flanders.

·1577 Gerardus Mercator, in a letter to John Dee (April 20th) shares details he culled from the Inventio Fortunato about the information of a Flemish priest in Greenland in 1364 who knew of both northwest and northeast passages to Asia

·1577-1640Peter Paul Rubens, Flemish painter

·1579 The Union of Utrecht, a mutual defensive pact unites all the Dutch-speaking provinces against Spain, is signed by Holland, Zealand and parts of Utrecht and Groningen (January 23rd) and then by Ghent, parts of Friesland, Guelders and Utrecht as well as all of Ieper, Antwerp and Breda (February 4th); George Calvert (later, Lord Baltimore and founder of the English colony of Maryland), a grandson of refugees from Antwerp, is born in England.

·1579-1584Willem I, prince of Orange-Nassau, serves as first stadhoulder – appointment negotiated and promoted by Philip Marnix of Brussel

·1580 The Union of Utrecht is signed by Bruges, Lier, the city of Groningen, Zutphen, and Guelders (February) as well as Overijssel and Drenthe (April). Crowns of Spain and Portugal united under Philip II

·1581Act of Abjuration (later the basis of American Declaration of Independence) declared: drafted by four men, three of whom Flemish; representatives of the United Provinces (led by Philip Marnix of Brussel) abjure their oath of allegiance to Philip II at The Hague; Johannes De Laet born at Antwerp.

·1582-1612 Emanuel Van Meteren of Antwerp (son of Jacob, first cousin of Ortelius and Daniel Rogers), is appointed Dutch Consul at London

·1583 Samuel Blommaert is born at Antwerp (August 21st)

·1584Willem I, prince of Orange-Nassau, assassinated at his home in Delft (July 10th)

·1584-1625Prince Maurits of Orange-Nassau assumes the inherited stadholdership

·1588Spanish Armada defeated (August 8th); initial surprise lost when two Flemish sailors escape the Armada and alert the English

·1590 Willem Usselinckx of Antwerp returns from a pro-longed sojourn in the Azores and the Iberian Peninsula with wealth and a plan to defeat Spain

·1594 Petrus Plancius is awarded a patent for a navigational solution to determining longitude at sea; largely under Petrus Plancius’ urging, the Compagnie Van Veere is established to seek out trade in the Far East.

·1595 “The placing of the compass-card in a fixed position beneath the needle, as in miner’s dials, surveying instruments, and opticians’ compasses, appears to have originated with Stevinus [Simon Stevins] of Bruges about the year 1595.”

·1598-1599The first real circumnavigation Netherlanders thru the Strait of Magellan led by first Simon de Cordes (a Zuidnederlander, who commanded the ship “de Liefde” which was piloted by Will Adams and made it to Japan) and then Jacques Mahu and financed by Johan van der Veeken of Mechelen as well as by Antwerpenaars Isaac and Simon LeMaire and Balthasar Coymans (who invested 18,000 guilders in the V.O.C.).

·1602United East India Company chartered by the States General of the United Provinces (March): Subscriptions taken over 5 month window (April 1st thru August 31st); largest chamber is Amsterdam with 57% of capital; it is run out of Antwerp emigres’ Dirck Van Os’ house half of all shareholders are “Zuidnederlanders” and 6 of the top 8 shareholders are as well.

·1605 Cecilius Calvert, son of George Calvert (later, Lord Baltimore), grandson of Flemish émigrés from Antwerp, is born in London (August 8th). Cecilius becomes the first proprietor of Maryland a Roman Catholic refuge, and it is for him that the city of Baltimore (established 1729) is named.

·1606 The Virginia Company established (April 10th) with investors including George Calvert (later, Lord Baltimore); the ship “de Witte Leeuw” (partially owned by Hons Honger of Antwerp), captained by Hans Lonck/Loncq of Roosendaal, trades and raids in the St. Lawrence Seeway for furs and fish (April-December).

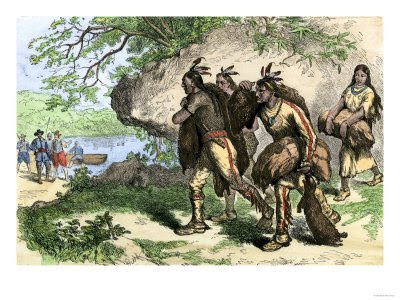

·1607The Virginia Company establishes Jamestown, which includes some Anglo-Flemings, such as John Ganne (May 14th)

·1609 Dirck Van Os of Antwerp establishes the Bank of Amsterdam (Amsterdamsche Wisselbank) which later becomes the model for Alexander Hamilton’s Buttonwood Agreement of 1792 (January 31st); Henry Hudson, in command of the East India Company ship Halve Maen, recruited, financed, and advised by Flemings, departs Amsterdam (April 4th) to find a Northeast Passage to Asia; Pieter Winne of Ghent (later of Nieuw Nederland) baptized at St. Baaf’s Cathedral (April 14th); Twelve years' truce with Spain (April 23rd); founding of the bank of Amsterdam by Dirck Van Os of Antwerp; Hudson ultimately explores North American coast from Delaware Bay to the upper Hudson as far as present-day Albany (Sept 3rd to October 22nd) and makes return landfall at Dartmouth, England (November 7th).

·1610 Beginning with Arnout Vogels of Antwerp (July 26th), Flemish merchants in Amsterdam send ships to exploit Hudson’s “discovery”

·1611 Arnout Vogels with fellow Antwerpenaars Francoijs and Lennaert Pelgrom charter the 120 ton (60 lasts) ship “St. Pieter” to trade for two months in New Netherland [likely Adriaen Block’s first voyage to New Netherland] (May 19th); Emanuel Van Meteren publishes the first written account of Henry Hudson’s “discovery” in his book Belgische ofte Nederlantsche Oorlogen en de Geschiedenissen

·1612 Adriaen Block purchases for Arnout Vogels and the Pelgrom brothers, the 110 ton (55 last) ship “Fortuyn” to sail to New Netherland (January 12th); Emanuel Van Meteren of Antwerp dies at London (April 18th); Govert Loockermans, later of Nieuw Nederland, baptized at St Pietrskerk in Turnhout (July 2nd);

·1613 Francoijs Pelgrom, in a letter to his wife, says that the just returned voyage by Adriaen Block on the ship “Fortuyn” was “a better voyage even than last year” (July 30th); Arnout Vogels and the Pelgrom brothers, the first of the “Voorcompanieen” to define the region that later is called New Netherland, calls itself (August)“the Company of lands situate[d] between Virginia and Nova Francia” and has an exclusive license to exploit the area from Prince Maurits, which the Prince later rescinds (September 23rd) and admonishes disputing to work thru a solution under the arbitration of Petrus Plancius

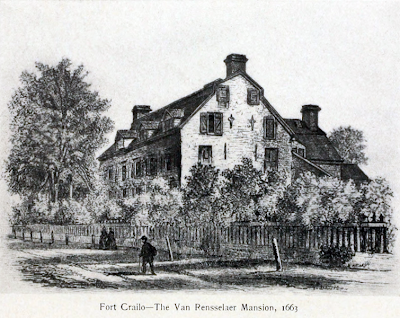

·1614The name New Netherland first appears in an official document; New Netherland Company licensed by the States General (October 11th); fur trading post Fort Nassau established on Castle Island, present day Port of Albany

·1615 New Netherland Company Charter officially begins (January 1st)

·1618 New Netherland Company Charter expires (January 1st)

·1618-1619Synod of Dordrecht; heavy representation by Flemish delegates including Franciscus Gomarus of Brugge, Petrus Plancius of Dranouter, Johannes De Laet of Antwerp and others (November 13th, 1618-May 29th, 1619); beginning of Thirty Years' War in Germany

·1619Beheading of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt [who opposes the establishment of the WIC and brokered the Truce with Spain], leader of the peace party, at the Hague (May 13th)

·1620 Arnout Vogels of Antwerp, the first to exploit New Netherland, dies (May 16th); the Pilgrims arrive off of Massachusetts and sign the Mayflower Compact (November 11th) – including Isaac Allerton, later a close friend and business partner of the wealthiest man in Nieuw Nederland, Govert Loockermans of Turnhout; George Calvert (later Lord Baltimore) of Antwerp extraction, purchases a tract of land on Newfoundland to establish a colony of Christian freedom he calls "Avalon".

·1621End of the Twelve years' truce with Spain (April 23rd); patent granted for the West India Company [WIC] by the States General (June 3rd, effective July 1st); George Calvert (later Lord Baltimore) of Antwerp extraction, sends his first colonists to the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland, arround a site called Ferryland (August); the States General permits a partnership led by Hans Hontom (or Houton) of Antwerp to send his ship “de Witte Duyf” under the command of Hontom’s brother Jan to New Netherland (September 13th); the States General permits a partnership led by Petrus Plancius to send two ships to New Netherland – one to the Hudson and the other to the Delaware – as long as they return by July 1622 (September 24th)

·1622 Petrus Plancius dies at Amsterdam (May 25th); the largest single investor in the W.I.C. (100,000 guilders) is the Antwerp émigré Guillielmo Bartholotti and more than half of all the 7 million+ guilders in capital raised is from the Amsterdam Chamber which is dominated by Flemings and Brabanders (and directs the activities for New Netherland); Samuel Blommaert of Antwerp is appointed a Director of the Amsterdam Chamber of the W.I.C. (October); census data show that more than half of the populations of Haarlem, Leiden and Middleburg are of Southern Netherlands origin and that even large cities like Amsterdam and Rotterdam are more than one third immigrants from modern day Belgium; George Calvert (later Lord Baltimore) of Antwerp extraction

·1623 George Calvert (later Lord Baltimore) of Antwerp extraction, is awarded all of Newfoundland as his "Province of Avalon" by James I (January); Adriaen Jorisz Thienpont (born at Oudenaarde) appointed the first Director General of Nieuw Nederland (June 20th)

·1624First colonists – 24 Walloon and 6 Flemish families – sail on the ship called “Nieu Nederlandt” and arrive in New Netherland where they are settled at Fort Orange (Albany), the mouth of the Connecticut River, on Manhattan Island, and on High Island (Burlington Island) in the Delaware River (April); Cornelis May, as senior skipper, becomes first director of New Netherland science of international law;

·1625-1647 Prince Frederik Hendrik becomes stadhoulder upon death of Prince Maurits (dies April 25th)

·1625Willem Verhulst departs Amsterdam and is named Director General of New Netherland (April 22nd) Sarah Rapalje, whose father may have been a tailor at Antwerp, is the first European child born in New York (June 6th); Publication of De Jure Belli et Pacis, by the Dutch statesman and jurist Hugo Grotius, lays foundation for the freedom of the seas; publication by the Elsevir brothers of Leuven of Johannes De Laet’s Nieuwe Wereld (1st book to describe and use the term “Nieuw Nederland”); George Calvert made Lord Baltimore.

·1626 Daniel van Crieckenbeeck, commander at Fort Orange, killed while supporting a Mahican war party against the Mohawks; Peter Minuit replaces Verhulst as director (July 31st); purchases Manhattan Island (some sources say May 24th but others suggest August 10th); moves settlers from Fort Orange, Connecticut, and Delaware to Manhattan

1627 George Calvert, 1st Lord Baltimore and a descendant of Antwerp, arrives at Ferryland, the Province of Avalon, Newfoundland(July 23rd)

·1628Piet Heyn captures Spanish silver fleet for the W.I.C. (September 8th); Samuel Godijn of Antwerp, Samuel Blommaert (both of Antwerp), and Kiliaen Van Rensselaer agree to hire two men and send them to New Netherland to purchase land from the Amerindians (December)

·1629Samuel Godijn of Antwerp, Samuel Blommaert of Antwerp, and Kiliaen Van Rensselaer formally announce to the Amsterdam Chamber of the W.I.C. their intention to plant a colony or colonies at New Netherland (January 13th); "Freedoms and Exemptions," establishing the patroonship plan of colonization, granted by the Lords XIX of the W.I.C. (June 7th); Samuel Blommaert of Antwerp resigns as a Director of the Amsterdam Chamber of the W.I.C. (June 30th)

·1630 Messrs Blommaert and Godijn of Antwerp with Kiliaen Rensselaer (and Albert Burgh) establish a partnership for a colony on the “South River” (February 1st); Michael Paauw of Ghent granted a patroonship (on the site of Jersey City, New Jersey) called “Pavonia” (July 13th); Samuel Godyn/Godijn of Antwerp granted a patroonship at Cape Hinlopen/Delaware River Bay ” (July 15th); Michael Paauw of Ghent granted a patroonship for Staten Island (August 10th); A new partnership is formed by Messrs Blommaert, De Laet and Godijn of Antwerp with Kiliaen Rensselaer (and others) for Rensselaeswyck (October 1st); A new partnership is formed by Messrs Blommaert, De Laet and Godijn of Antwerp with Kiliaen Rensselaer (and others) for the establishment of a colony on the South (Delaware) River (October 16th); Michael Paauw of Ghent granted a third (New Jersey) patroonship at “Ahasimus” (November 22nd); Johannes De Laet of Antwerp joins with Samuel Godijn of Antwerp, Samuel Blommaert of Antwerp, and Kiliaen Van Rensselaer to form a general partnership (October).

·1631 First colonists for Swaenendael landed at Blommaert’s Kill/Lewe’s Creek (March?); Samuel Godyn/Godijn and Samuel Blommaert [and later including Johannes De Laet] – all of Antwerp – were granted a patroonship at Cape May (June 3rd); Kiliaen Van Rensselaer granted the east side of the Hudson River later called Rensselaerwyck (August 6th); Kiliaen Van Rensselaer granted the west side of the Hudson River also included in Rensselaerwyck (August 13th) – he includes the Antwerp natives Samuel Godyn/Godijn, Samuel Blommaert, and Johannes De Laet.

·1632George Calvert, 1st Lord Baltimore, grandson of Antwerpenaars and Founder of the English colony of Maryland, dies in London (April 15th); Pieter Minuit removed as the Director General of New Netherland and replaced by Bastiaen Jansz Crol; the Delaware River colony of Swaenendael (population 34) is destroyed by Indians (November 18th).

·1633 JanBaptist van Antwerpen, gunners mate on the ship “Nieu Nederlant:, brings back to Patria 23 beaver pelts for private trading (April 7th); The very first military force to defend New Netherland of 104 soldiers arrives with the new Director General Wouter Van Twiller on the Zoutberg (April) accompanied by the captured Spanish yacht St. Martyn (commanded by Juriaen Blanck of Flemish origins) on which is also Govert Loockermans of Turnhout (April); Samuel Godijn dies (September 29th); first purchase of land from Indians outside Manhattan (on the Schuykill) is witnessed by Govert Loockermans (October 24th).

·1633-1638Wouter van Twiller, director of New Netherland (April)

·1634 Adriaen Vincent/van Sant, born at Aecken near Ghent, arrives in New Amsterdam from London on the English ship “Mary&John”; the first colonists from England arrive to establish the Royal Colony of Maryland, under the proprietorship of Cecilius Calvert, 2nd Lord Baltimore, and of Antwerp descent (March 25th); Hans Hontom, originally of Antwerp, and who first arrived in New Netherland in 1611, is killed by Cornelius vander Vorst in a knife fight at Renseselaerswyck (April);“Pretensions and Demands of the Patroons of New Netherland” delivered to the Directors of the West India Company (June 16th);

·1635 The W.I.C. agrees to Michael Paauw of Ghent’s terms to buyback his patroonships for Pavonia and Staten Island (January 1st)

·1636 Samuel Blommaert of Antwerp becomes an agent/advisor of the Swedish government (November).

·1637 Samuel Blommaert of Antwerp sends Pieter Minuit to Sweden to prepare for a Swedish colony near the old Swaenendael patroonship in Delaware (February).

·1638Peter Minuit hired by Swedish South Company, establishes New Sweden on the Delaware River (Wilimington, Delaware); Minuit lost at sea while returning to Sweden; Johannes De Laet proposes an official plan for the colonization of Nieuw Nederland (August 30th)

·1638-1647Willem Kieft, director of New Netherland

·1639 The sale of muskets or gunpowder to Amerindians in New Netherland is forbidden on pain of death (March 31st); The W.I.C. opens fur trade to everyone (May); Isaac Bedlow, with origins in Maldegem (near Middleburg, East Flanders), and who became the owner of Bedloe’s Island (where the Statue of Liberty stands) and Pieter van der Linde (from Belle Flanders, a surgeon the ship “De Liefde” and later, in 1648, schoolmaster) arrive in New Netherland.

·1640 Emmigrants to New Netherland are no longer required to pay for their passage over (May);Cornelis Melyn of Antwerp receives the rights of patroonship for Staten island (July 3rd); Michael Pauleszen van der Voort (from Dendermonde, East Flanders) marries Maria,Rapalje (daughter of Joris and sister of Sara – 1st European born in New York) at the Dutch Reformed Church in New Amsterdam (November 18th)

·1641 Cornelis Melyn of Antwerp arrives at New Amsterdam on the ship “Eyckenboom” and establishes his colony at Staten Island (August 20th)

·1642 AnnekenLoockermans of Turnhout, sister of Govert, marries Olof Van Courtlandt (February 26th) in the Dutch Reformed Church of New Amsterdam; Govert Loockermans is granted the Brooklyn Ferry as well as a a house and lot in Manhattan (March 26th);Cornelis Melynis granted “the major part” of Staten Island (June 19th); Pieter Loockermans (brother of Govert) arrives in New Netherland.

·1642-1654Johan Printz, governor of New Sweden

·1643 Stephanus Van Courtlandt, son of AnnekenLoockermans of Turnhout and nephew of Govert Loockermans (and brother of Maria Van Rensselaer) and the first, native-born mayor of New York City is born in New Amsterdam (May 7th)

·1643-1645Kieft's war with the Indians around Manhattan Island

·1644 Cornelis Melyn of Antwerp awarded a double lot in Manhattan along the Strand (April 28th); Adriaen Vincent “from Aecken near Ghent” awarded a double lot in Manhattan on Ditch (later Broad) Street (June 1st); Pieter (vander) Linde of Belle, Flanders, marries Martha Chambert of Newkirk, Flanders (July 10th); Johannes De Laet publishes a chronicle of the W.I.C. (with details relating to New Netherland) in his Histoire ofte Iaerlijck Verhael.

·1647 Wilhelmus Beekman, the longest serving mayor of New York, and a grandson of Deinze (thru his maternal grandfather Willem Baudartius) and Brugge (thru his paternal grandfather Hendrik Beekman) arrives in New Netherland

·1647-1650Prince Willem II as stadholder

·1647Petrus Stuyvesant becomes director general of New Netherland, Curaçao, Bonaire, Aruba, and other dependencies in the Caribbean; WIC ship Princess Amalia lost in Bristol Bay, former Director Kieft and Domine Evardus Bogardus drowned with 82 others

·1648Peace of Westphalia, settling Eighty Years' War with Spain; end of Thirty Years' War

·1649Simon Joosten of Meerbeke (near Aalst) marries Marritje Simons at the Dutch Reformed Church in New Amsterdam (August 4th); Johannes De Laet of Antwerp dies (at Leiden).

·1650States General, opposing authority of princes of the house of Orange, assume control over Dutch general policy; Hartford Treaty, settling boundary dispute between New Netherland and New England

·1651Stuyvesant abandons Fort Nassau (Gloucester, New Jersey); replaces it with Fort Casimir (New Castle, Delaware) below Swedish Fort Christina; Teunis Janszen Couverts (of Loemel in Limburg) arrives in New Netherland; Jan Coster van Aecken near Ghent (Beverwyck blacksmith and fur trader) marries Else Janse (); Samuel Blommaert of Antwerp dies at Amsterdam (December 23rd).

·1652-1654First Anglo-Dutch War

·1653 Isaac Bethloo (later Bedloe) marries Lysbeth Potters of Batavia, East Indies at the Dutch Reformed Church in New Amsterdam (May 16th); Jan Corneliszen Van Cleef, grandson of Martin from Antwerp and ancestor of actor Van Cleef, arrives in New Netherland; Construction of defensive wall across Manhattan Island (Wall Street) after threat of invasion from New England

·1654Swedes under new governor, Johan Rising, capture the Dutch post Fort Casimir on Trinity Sunday, rename it Fort Trefaltighet (Fort Trinity); Samuel Blommaert of Antwerp dies, still a part owner of Rensselaerwyck .

·1655 Joris Stephenszen of Brugge marries Geesje Harmens at the Dutch Reformed Church in New Amsteredam (May 5th); Nicasius de Silla of Mechelen marries Tryntje Crougers in New Amsterdam (May 26th); Stuyvesant conquers New Sweden in the Delaware Valley; Indians around Manhattan attack New Amsterdam, Pavonia, and Staten Island in a conflict called the Peach War.

·1656 Daniel Janszen Van Antwerpen of Beverwyck and later Schenectady, marries Maria daughter of Symon Symonsen Groot; Jan Tibout of Brugge settles near Ft. Casimir on the S. Delaware River; Pieter Janszen Loockermans of Turnhout purchases a house in Beverwyck (November 1st)’ Johanna De Laet, widowed daughter of Johannes De Laet, arrives in New Netherland.

·1657 Gabriel Corbesye, from Leuven, marries Teuntje Straetsmans in New Amsterdam (June 15th); Fernand Willays (born in Kortrijk) and Joost Koochuijt [sometimes listed as Kockuyt] born at Brugge arrive on the ship “De Verguilde Otter” in New Amsterdam (December 22nd)

·1658 CornelisVan Langevelt of St. Laurens, East Flanders, marriesMairitie, daughter of Jan Corneliszen Jonkers at the Dutch Reformed Church in New Amsterdam (January 19th); Christaen Toemszenof Strabroeck (Stabroek, Antwerpen) marries Engeltje Jacobs at the Dutch Reformed Church in New Amsterdam (February 10th); Jan Evertsen of Lokeren, East Flanders and Anthony de Mil, grandson of Mennonite Bruggelings who emigrated to Haarlem, arrive in New Netherland on the ship “de Verguilde Bever” (May 17th); Philippus Jacobus Schooff of Antwerp marries at the Dutch Reformed Church in New Amsterdam Jannetje Toenis Kay (July 26th); Jacobus Van Courtlandt, son of AnnekenLoockermans of Turnhout and brother of Stephanus, and grandfather of the first U.S. Chief Justice, John Jay, is born at New Amsterdam.

·1658-1663Esopus Indian War in New Netherland

·1659 Johanna De Laet (daughter of the Antwerpenaar Patroon and WIC Director Johannes De Laet) marries (Jeronimus Ebbing) in the same church in New Amsterdam on the same day (February 22nd) as Jan Guisthout Vander Linden of Brussels (who marries Jannetje daughter of Barent Balthus Van Kleeck from Haarlem); Pieter Follenaer (of Hasselt, Limburg) arrives in New Amsterdam on the ship “De Bever” (April); Karel de Beauvois (born in Leiden) lists himself as Flemish (father from Ghent) when he arrives at New Amsterdam; WIC soldier Jacob Farmont (born in Brussels) marries Annetje Andries in New Amsterdam (September 5th).

·1660 Anries Pieterszen a soldier and Willem Vanschure (both born in Leuven), Willem Vanderbeke (born in Oudenaarde), Ludovicus Aerts (born in Brugge), Jean Verele [Verhelle?] (born in Antwerp), and Pieter Bayard (born in Nieuwpoort, West Flanders) arrive in New Netherland on the ship “De Moesman” (March 9th); Ferdinandus Van Sycklin (born in Ghent; ancestor of U.S. Civil War general Dan Sickles) marries Eva, daughter of Anthonee Van Salee [the infamous Dutch pirate and convert to Islam] in New Amsterdam.

·1661 Jan Doske, a soldier born in Tongeren, Limburg, marries Styntje Klinckenborgs from “Aken” (February 19th); Jacob Abrahamsen, born in Zandvoorde, West Flanders, arrives in New Netherland on the ship “Johan de Doper” (May 9th); Jan Evertszen of Lier, East Flanders, arrives in New Netherland; Cornelis Stevenszen Muller of Turnhout marries Hillitje Loockermans (niece of Govert, daughter of Pieter) in Beverwyck.

·1662 Jan de la Warde, listed as a Fleming, (born in Antwerp), arrives in New Netherland on the ship “De Vos” (August); Balthus Loockermans [brother of Govert] is in New Amsterdam; Harmanus Van Hoboken (schoolmaster 1555-1559 in New Amsterdam) marries Claertje Pieters (October 28th) at the Dutch Reformed Church.

·1663 Alexander Stilteel of Duynkerken marries Maria Burchhardts in New Amsterdam (February 10th); Jan Gysberstzen Meteren [grandson of Antwerpenaar Emanuel Van Meteren], Teunis Janszen Lanen van Pelt (from Overpelt, Limburg), his four children and brother Matthys Janszen Lanen van Pelt (from Overpelt, Limburg) and Jan Bastiaenszen van Kortryk [Kortrijk], ancestor of First Lady Elizabeth Kourtright (President James Monroe’s wife) arrive in New Amsterdam on the ship “de Roosebloom” (March 15th).

·1664 Meynard Jurnay of Duynkerken marries Lysbeth Durmon in New Amsterdam (May 16th); Carel Enjart “from Flanders” arrives in New Netherland (descendants known as “Injyard”); English naval force funded by the Duke of York and Albany captures New Netherland in a surprise attack during peace time

·1665-1667Second Anglo-Dutch War

·1665 Christina Pieters “Van Sluys in Vlaenderen” marries Johan Letelier (April 26th); Francoys Rombout (the first New York mayor born in what we now call the Flemish Region, Hasselt, Limburg) marries Aeltje Wessels; Admiral Michiel Adriaansz de Ruyter retakes most of the WIC trading posts lost previous year to English in Africa; De Ruyter's plans to retake New Netherland aborted

·1667 Marye Van Hoboken marries Otto Laurenszen at the Dutch reformed Church in New Amsterdam (February 20th); Admiral Abraham Crijnsen retakes former Dutch colonies in the Guianas (Wild Coast of South America) seized by the English

·1670 Jean Crocheron (born in Zele, East Flanders) arrives at Staten Island; Ms. Beelitie Jacobs of Brugge marries Frans Hendrickszen of Breevoort (November 4th)

·1672-1674Third Anglo-Dutch War

·1673New York captured by Dutch naval force; New Netherland restored as a Dutch colony; Anthony Colve, grandson of Bruggelings, becomes Nieuw Nederland’s final governor.

1674 Lieutenant Herman Anthony Hubert (“from Hulst in Flanders”) marries Lucretia Rodenburg (January 21st) in New Amsterdam; WIC soldier Pieter Schamp of Ghent marries Jannetje, daughter of Dirck Volkertzen in the New Amsterdam Dutch Reformed Church (October 24th); New Netherland becomes New York again as a result of the peace of Westminster (November 10th)

.jpg)

Several factors accelerated the expansion of the Flemish column within the ‘Protestant International’. As arcane as it may seem, fashion was one of these factors. Paris even then set the pace for modish dress in the Western world and in the second half of the 16th century there was an increasing push toward felt hats (made from treated fur) for men. Siberian furs, supplied by Flemish expatriate merchants like Olivier Bruneel from Narva, were shipped through Antwerp.

Several factors accelerated the expansion of the Flemish column within the ‘Protestant International’. As arcane as it may seem, fashion was one of these factors. Paris even then set the pace for modish dress in the Western world and in the second half of the 16th century there was an increasing push toward felt hats (made from treated fur) for men. Siberian furs, supplied by Flemish expatriate merchants like Olivier Bruneel from Narva, were shipped through Antwerp. Once on site, the Flemings jumped right in. As early as the 1570s (and possibly earlier), Flemish Protestants in France were financing trade to North America. In the words of one Canadian historian, this was another case of “economic interlacing [that] was the presence in French port towns on the Atlantic of ‘Flemish neighbourhoods’”.

Once on site, the Flemings jumped right in. As early as the 1570s (and possibly earlier), Flemish Protestants in France were financing trade to North America. In the words of one Canadian historian, this was another case of “economic interlacing [that] was the presence in French port towns on the Atlantic of ‘Flemish neighbourhoods’”. It’s All in the Family

It’s All in the Family